JN: How long have you lived in the Catskills?

BH: I was actually born here and then I moved away for college. I lived in New York City for a while and Boston for a while. I came back here and practiced law for a bit and then moved to the Finger Lakes area when our first child was born. I lived in Dutchess County for a while and came back about four years ago, right after Hurricane Irene.

So you like to travel?

No, I actually don’t like to travel, but my first wife was a navy brat and she did like to travel, so we did.

I was having a conversation with somebody else about that, about how young people are moving away and how we can keep young people in the region.

And that’s been an issue ever since I went to school here. I can remember the Rotary Club had about eight of us come down from my class in 1976 and asking us what would it take for [us] to come back here, but in being 18 years old, we didn’t really have an answer at the time.

And didn’t care.

[Laughs] And didn’t really care, but it certainly is a big problem. There weren’t a lot of opportunities then and there are even fewer opportunities now for good jobs.

You have to make your own opportunities here don’t you?

You really do. Most people I know, who are able to stay here and live fairly well, work two or three different jobs and at least one of those is something that they thought up and invented on their own.

You have to basically create a market for yourself and then exist in that market and work within it.

One of the reasons I went to law school is because it was one of those things that I thought that you could do in this community and make a fairly decent living, but back in 1976 when I graduated from school, there were actually a number of factories around that paid living wages to their employees. There was a bat handle factory in Arkville and there was a veneer factory in Fleischmanns, but those are gone. The active farms, which didn’t really pay a living wage, but if you lived on a farm, you managed to have a quality of life you often couldn’t get in other places. The hours were pretty long. Those are all gone.

Why do they go?

One, the dairy business – the price paid to farmers for milk has not gone up in the last forty years.

That’s terrible.

The price increases have all gone to the middlemen and not to the farmers and in order to be competitive and productive the farmers had to scale up. In the Catskills, that’s because of the type of land we’ve got, it’s really hard to scale up and still be successful. There were a couple of farms over on the West Branch of the Delaware that were able to do it over in the Stamford area.

What do you mean by scaling up?

When I was a kid on this farm, we had dairy cows until about 1964 or 1965 and our herd consisted of 38 cows, which was something that two or three men could milk and take care of and care for. I’m not sure what size is profitable but typically things happen like you’d have to have hundreds of cows in order to do it. A lot of times, instead of being put out to pasture they were being in kept in what were called feedlots, which are really not very pleasant. Instead of milking twice a day sometimes they were on three times a day, and the parlour goes full time, the cows are run through the milking parlour so that somebody is always milking a cow on the farm.

That’s exhausting for the cow.

It’s exhausting for the cows. It’s exhausting for the people. On our farm, back in the day, there would be the morning milking and the evening milking.

The answer now is, if you really want to help a farmer, go directly to him and buy from him.

It really does help because that way they get to retain the profit and they get to retain the value of what they have produced.

Growing food is a high-risk business and the farmer shouldn’t have to be the one carrying all the risk.

The farmer frequently is the one carrying all the risk. The people who are in the distribution and sales part of it – they view it from the customer’s viewpoint. They know how many units they are going to sell over a given period of time and they don’t take any risk at all. Their prices will vary. You’ll probably notice the price of eggs went up recently.

I didn’t notice. Whatever the farmers wants me to pay, I will pay it. I’m like, whatever you need. I’ll pay you whatever you want.

Right. Well, the history of this area is interesting in that regard because originally it starts out with what are largely subsistence farms where families are moving here following the Revolutionary War and they are just little homesteads. They are just trying to grow enough to feed themselves. If they exported anything from around here, it was typically something like cheese, butter, wool: things that could store well and be taken on a two day trip to the Hudson River where they could be put on a boat to sell in Albany or New York City. And then, right after the Civil War, the railroad comes through and now all those farms, which had largely been subsistence farms can ship their food products to New York City and this area becomes a very profitable farming area. Farms become big business for the time. And they do fairly well. Most of what you see in terms of buildings around this farm were built in the post-Civil War period because the family was making a lot money off the agricultural business. They were also able to bring in things such as the equipment for our cider mill, engines and that sort of thing. That let them expand on a small industrial level. Then in the 1920s what happens in this area is that refrigeration comes in. These farmers that had a captive market in New York City are now competing with farmers out in Wisconsin with their milk and cheese. They’re competing with growers out in California for produce.

And the market suddenly becomes enormous.

The competition is enormous. The prices start to slowly drop and you see a slow decline of the farms, from that time on, in the Catskills.

So how do we get the farms back again?

I don’t know. I have high hopes but I don’t know that they’re based on analytical framework for the sustainable living – the idea that people are very interested in being able to repeat the process ad infinitum of growing on the land and preserving the land. As I think about it, I would be very happy to live in that kind of community where we all provide for each other’s needs. But I see a lot of money that gets sucked out of the area, through taxes to the state and federal and I’m not sure that we really get back in kind in services.

It costs a lot of money to employ someone in New York State.

It does.

You’ve got worker’s compensation, disability, mandatory overtime for some workers, health insurance…

[Health insurance] has roots in history. That actually goes back to World War II. During that period, the federal government set wage rates because they didn’t want companies competing for different workers when they were trying to get the manufacturing process up and running that they needed for war materials. Of course, it’s unrealistic from an employer’s point of view not to be able to complete, but since you couldn’t pay a welder any more than the competition could pay a welder what they came up with was paid time off and health insurance. That’s when employers really got into the benefits because with the benefits they could compete for better workers. That’s how health insurance started.

What did health insurance look like after WWII? Were very large companies paying for people’s hospital care?

I suspect it was employers simply paying for hospital care, back then it was a couple of hundred dollars to go to the hospital and have a baby. From the employer’s point of view that wasn’t a big deal.

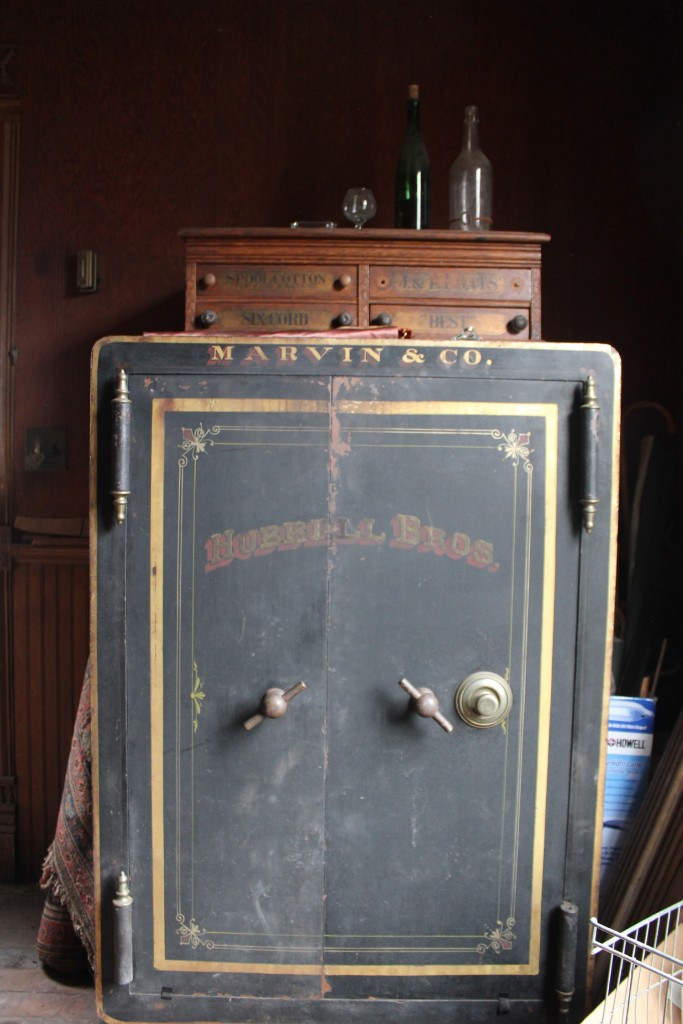

The Hubbell Homestead. How long has it been here?

I actually don’t know how long it has been here, but our family bought this in 1848. At that time, it already had a house and a barn; it was a working farm.

How big was it?

At that time it was probably 160 acres. Now it’s 260 acres. It goes from the river in the center of the valley, up to the top of the ridge.

What made you leave the area?

I went away to college. I picked a college that was in the middle of the mountains, Williams in Williamstown, Massachusetts in the Berkshires. Then I went to law school, with the idea that I wanted to come back here, live here and practice law. But I got married and we went to Boston and she got her MBA from Harvard and she really wanted to work in higher education finance.

You should start with high schools really because they don’t really teach personal finance in high schools.

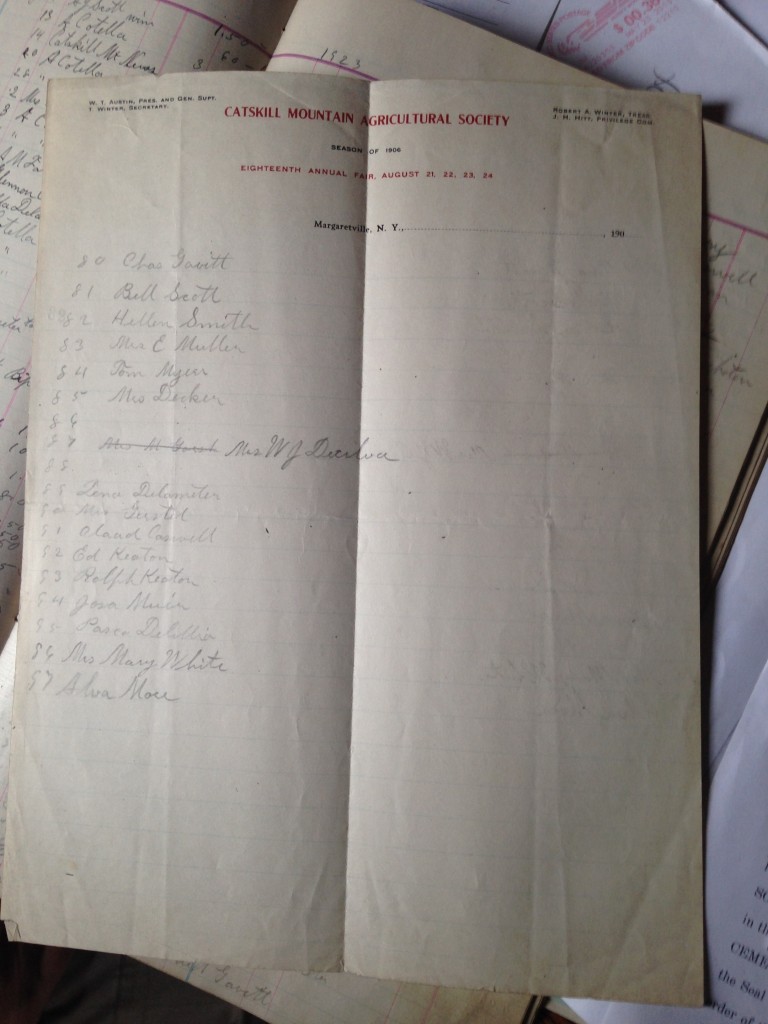

I never learned any personal finance, but I grew up in family where they were meticulous record keepers. So they kept ledgers of every penny they spent on any given day.

Do you still have those records?

Most of them are at the Delaware County Historical Society in Delhi. They were upstairs in a room where the roof had started to leak and I was worried, so we moved them. Some of the records dated back to when they bought the farm in the 1840s.

How does it feel to be part of a legacy like that?

Well, for one thing, when you grow up this way, you don’t know that it’s different elsewhere. For a long time, it never dawned on me that anyone who grew up on a farm didn’t grow up like this.

You don’t see that everywhere, where the family has been in situ for hundreds of years. We could probably do a series on the Hubbell History. It must be comforting to have your family around, because a lot of people move and travel.

It does. It gives a real sense of security to be near your family and have a piece of property that’s been in the family for this long. But when you get to my age when it becomes the responsibility of my generation to take care of it – which it is now – it can feel like a pretty overwhelming responsibility.

What sort of businesses do you have here? Is there an actual working farm?

Right now, we have started on raising animals for food, but it’s going to be an actual three or four-year process before we start. I hope to just break even on that and get the tax exemption. We really don’t see this as being a competitive farm. It’s more of a local, sustainable movement. We hope to be able to sell all of our food from here and sell it locally to local people.

Do you have a website?

We’ve actually already got a small website, but we’re not using it for publicity purposes. We sell a little bit of maple syrup.

Well, I meant a website for customers like me. Supermarkets are a relatively new thing. They started in the 40s and before that everybody grew most of their food themselves. I see that the farmers are struggling, committing suicide and in need of advocates.

I would feel terrible if I was going to lose this farm, but that’s what happened to a lot of farmers. We were very fortunate that the family never borrowed against it. There was never a mortgage on the farm, so we never had to worry about payments. But it’s easy, especially on certain types of farms with certain types of product. You borrow to do your planting and, if you have a bad season, that could be the end of you and the end of a farm that’s been in the family for generations.

So I don’t see the supermarkets doing too badly though.

No, they all seem to survive, but they survive because they have a steady stream of customers and they mark their products up so that the farmer tends to be at the mercy of what supermarkets are willing to pay.

Exactly. So back to the question: how do you keep young people here?

One of the things you have to be able to do is pay them a living wage. By living wage I mean something that allows them to go out and purchase a house of their own, allows them to take a vacation and covers their healthcare costs. I don’t think it’s just a local problem, but we don’t pay people enough money in this country. There’s a huge shift going on in terms of wealth and we’ve got a very small elite that has a fantastic, unimaginable amount of money and then we’re paying people $8 per hour. It was one thing when you were paying a high school kid $8 an hour, but we’re paying people in their thirties or forties $8 an hour and if I wanted to go out and hire people, I could hire people that would actually come and work for that wage.

It’s heartbreaking.

Right, because you can’t even rent an apartment on that.

No, you can’t. So, last question: what inspires you most about the Catskills?

Well, one is just the natural beauty. It’s just a wonderful place. Two, I genuinely like the people who are here and make up this area. I think it’s a little bit more laid back than the fast, urban-paced settings you find in New York City. I have an attachment to the land, particularly this land here. It’s being able to walk around where my ancestors have walked and do the things that they did – that’s a huge attraction for me.

Is there a thing as a day off in country life?

Yes, but you have to decide to take it. There’s always something to do here. That window needs to be replaced and I’ll have to get to it before winter.

It never-ending.

You have to take time off to enjoy where you are, whether you go fishing or just go for a walk to remind yourself of all the beauty around here.

Loved every bit of this article. The Hubbell family remind us every day what is important in life and in the NYS Catskills.

The salt of the earth

It’s great that you are getting ideas from this piece of writing as well as

from our argument made here.